Remembering Fred Branfman (1942–2014)

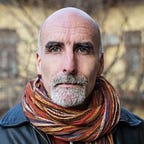

My friend Zsuzsa Beres is holding a commemoration in Budapest on the weekend of May 16–17, to celebrate the life of her late husband — and my friend — Fred Branfman, who passed away in September last year.

I won’t be in town next month, so I decided to offer a few memories of Fred as I knew him.

Fred Branfman and I met in Budapest in 1991. At the time I was an editor of Budapest Week, a weekly English-language newspaper.

It seemed to me Fred had stepped out of some kind of 1960’s fairy tale. He was a celebrated anti-war activist. He had served as a policy advisor to former California governor Jerry Brown, Tom Hayden and Gary Hart. He had authored Presidential-level policy papers. By that point in his life, Fred Branfman was no stranger to the corridors of power.

So why did this guy want to meet me?

I was honored — and somewhat baffled — to learn that Fred wished to submit an essay to our newspaper entitled “In Search of the Hungarian Soul.” I recall that it was an insightful piece, but for the life of me I cannot find it archived anywhere.

As we sat down for beers in a Budapest cafe, Fred put me off guard by peppering me with questions: Why was I living in Budapest? How did I get here? What mattered most to me in life?

Fred Branfman was genuinely interested in knowing me as a person.

And so began a free-ranging conversation that — as best as I can recollect — must have lasted two or three hours.

The birth of an anti-war activist

Fred’s unlikely story, as he told it to me, began in a village in Laos in the late-1960s where he served as an educational advisor, learned the Laotian language and then — as if the hero of a Hollywood film — played a key role in uncovering one of the greatest war atrocities of the 20th century: America’s Secret Air War in Laos.

Fred had stumbled upon the most extensive bombing campaign in human history — an operation totally unknown to the American public at the time.

From 1964 to 1973, the U.S. military dropped nearly two million tons of ordinance on Laos, which breaks down to a planeload of bombs every eight minutes, 24-hours a day, for nine years.

Fred had been called to the capital, Vientiane, to interpret for a reporter interviewing refugees arriving from the Plain of Jars. Hearing their stories Fred was first horrified and then morally outraged at the injustices being perpetrated — in his name — by his fellow countrymen:

I had learned of countless grandmothers burned alive by napalm, countless children buried alive by 500-pound bombs, parents shredded by anti-personnel bombs. I had felt pellets from these bombs still in the bodies of the refugees lucky enough to escape, interviewed people blinded by the bombing, seen napalm wounds on the bodies of infants. I had also learned that the U.S. bombing of the Plain of Jars had turned a 700-year-old civilization of some 200,000 people into a wasteland, and that its main victims were the old people, parents and children who had to remain near the villages — not the communist soldiers who could move through the heavily carpeted forests, largely undetectable from the air. And I had soon also discovered that U.S. Executive branch leaders had conducted this bombing unilaterally, without even informing, let alone obtaining the consent of, Congress or the American people. And I realized that these devastated Plain of Jars refugees were the lucky ones. They had survived. U.S. bombing of hundreds of thousands of other innocent Lao was not only continuing but escalating.

I know many Americans of my generation who share this feeling: a deep disillusionment and anger over the contractions between the principles of America’s founding fathers and the actions carried out by its leaders — supposedly in defense of those principles.

I had grown up believing in American values but this bombing of innocent civilians violated every one of them. Looking at U.S. executive branch leaders from the perspective of a Lao refugee camp, I had learned in a few weeks that they were the enemy of human decency, democracy, human rights and international law abroad, and that in this real world might made right and crime paid. However much one believed America was a “nation of laws not men” at home, it was clearly a nation of cruel, brutal and lawless men in Laos.

It is not easy to read these words and remain indifferent. That was the point. Fred’s made it his mission to give a voice to the world’s “unpeople” — the anonymous victims in the crosshairs.

This is the quality I love most about Fred Branfman. Just as he truly desired to know me as a person that afternoon we met, he also wished that all of us would finally get it that the casualty counts have human faces:

Once you knew that innocent people were dying, how could you justify to yourself doing anything other than trying to save their lives?

It took courage to take this position. While in Laos, Fred was followed by the CIA and the Laotian secret police and eventually deported. He later snuck into South Vietnam to investigate the conditions in U.S.-run prisons. He was even blamed by American Ambassador Graham Martin for the fall of Saigon.

Fred found a unique way to give faces to the victims by collecting first-person accounts from survivors of the bombing in Laos. First published in 1972, his book “Voices from the Plain of Jars” was reissued in 2013.

Rebirth as a peace activist

Fred Branfman worked relentlessly to end the atrocities in Indochina. That led him to a career in politics. However, by the time I met Fred his heart was no longer in the game. He told me he had spent his last several years running think tanks.

Paraphrasing Fred’s own words, this is how a think tank works: Political interests provide funding to think tanks, which produce research data and policy statements to support those political interests.

At the age of 49, Fred Branfman had completely lost interest in his political career. I couldn’t relate to this at the time — I was a younger man then — but I have since experienced a similar transition. Letting go of the unnecessary. Turning the heart’s focus toward deeper, more profound matters.

That day we met, Fred was looking forward to celebrating his 50th birthday in Laos, which he considered his spiritual birthplace. Years later when visiting Laos for myself, I often thought of Fred and, in a way, felt myself retracing his footsteps.

Traveling in Laos, I came to understand Fred’s love and respect for the Lao people. A generation ago my fellow countrymen — acting in my name — had dropped two-thirds of a ton of explosives for every man, woman and child. Yet those gentle, unassuming people welcomed this American with their warm smiles.

Fred Branfman wasn’t always an easy man. In recent years, when he was living in his Budapest apartment by the Danube, I would pay him the occasional visit. From time to time the conversation devolved into grumpy political rants.

I preferred Fred’s gentler, more philosophical side. The conversations I enjoyed most had to do with his later pre-occupation with mortality, which he called “life affirming death-awareness.”

In his final years, Fred made it his spiritual practice to face the agony of his fear of death which, as he experienced it, transformed into a deep love for life:

Our present lives can be transformed to previously unimagined levels of aliveness and love by releasing the energy we now use to repress our pain about the prospect of our eventual death. Life-affirming death awareness makes us truly alive.

This is no Kumbaya spirituality; Fred’s path requires courage.

“We can only know real joy if we dare feel real pain,” he wrote. “Doing so makes us truly alive, not ‘happy.’”

Fred wrote extensively about his experiences at trulyalive.org, a website his wife and friends are working to develop further.

Fred also found a way to transmute at least some of his anger into forgiveness.

This is what Fred had to say about his fellow Americans who prosecuted the Secret Air War in Laos, carrying out atrocities that had outraged him so as a younger man:

[T]hey committed monstrous acts, killing thousands and thousands of innocent human beings, in violation of the rules of war. I say this without bearing personal animosity to the gentlemen in question in Laos. Indeed I see them today as rather interesting and often endearing chaps in their non-bombing Laos roles.

… And I say this without questioning their motivation. Indeed, I am perfectly willing to admit that it was, at least in many cases, no better or worse than my own. I have been persuaded that those on the ground who really hated communism were at least as ‘idealistic’ as those of us who opposed the war. And I am even more than willing to entertain the notion that I, too, am capable of acting monstrously in the unlikely event that the U.S. Air Force was placed at my disposition.

Fred Branfman began his life’s mission as an opponent of war: an anti-war activist. I believe that by the end of his life he was more of a proponent of peace: a peace activist.

Let us not forget

Just because Fred was able to forgive the perpetrators of the Secret Air War in Laos doesn’t mean that he ever found their deeds acceptable.

By its own admission, Central Intelligence Agency’s activities in Laos constituted “[t]he largest paramilitary operations ever undertaken by the CIA.”

While the agency’s official version of the story makes no mention of civilian casualties, it notes that by 1969 the number of air sorties had reached 300 per day. “Although the country eventually fell to the Communists, the CIA remained proud of its accomplishments in Laos.” (emphasis mine)

Fred Branfman made it his life’s mission to ensure the Central Intelligence Agency did not have the last word.

Watch this video to hear Fred tell the story in his own words. It will be seven minutes of your time well spent. At 0:45 Fred stands in front of the U.S. Congress to expose the secret bombing in Laos.

What you can do to help

Unexploded ordinance (UXO) continues to threaten a quarter of all villages in Laos. By the end of 2012, there had been at least 50,000 casualties (including 29,000 deaths) from incidents involving UXO. Each year, some 300 Laotians die — 40% of those victims are children.

To this day, less than 1% of these munitions have been destroyed.

The Mine Advisory Group is working to clear unexploded landmines and cluster bombs from Laos and other conflict regions. If you feel inspired to help, please consider making a donation.